I finally got a chance to start Adam Goodheart's 1861: The Civil War Awakening. The author spent some time detailing the life of the young Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the red-shirted Zouave killed in May 1861, as a focal point for his larger discussion on the ideals of the "generation of 1861." The young men who came of age just as the war began were an ambitious lot, full of ideals (thanks to Ralph Waldo Emerson), impressed by revolution and the possibility of war (thanks Kossuth and Garibaldi, etc.), willing to fight for their political beliefs, full of romantic notions (thanks to Sir Walter Scott), desirous to break with the older generation, and ardent to strike out in the world on their own and leave a personal mark. As I read through this chapter I couldn't help but think of our twenty-first president, Chester A. Arthur of New York.

Born in Vermont in 1829, Arthur was 31 years old when the war began, perhaps a little older than the generation Goodheart wrote about, but not by much. Arthur's biography confirms Goodheart's description of this cohort. Like his peers Arthur sought a clear break with his past. The son a Baptist preacher whose hot condemnations of slavery kept him on the move, Chet sought a life with more stability, greater wealth, and a lot less religion. It was a strong rejection of upbringing. He attended Union College in the 1840s and became a school teacher. This, however, only served to pay his bills while he prepared for a legal career. In 1854 he was admitted to the bar and moved to New York City, a place far removed from his old stomping grounds of small, poor towns of upstate New York and New England.

Arthur certainly left his father's religion in the dust. His mother complained about her sons's (both Chet and his brother William) lack of devotion, and the future president's own son Chester A. Arthur II believed his father possessed no religious convictions at all. On the other hand, some of the moralistic preaching sunk in. Chet considered slavery a moral wrong and did what he could to fight the evil institution. As a young attorney he worked on the Lemon Case, to free slaves who had escaped their Virginian master when he stopped in New York City on the way to Texas. Arthur also visited "Bleeding" Kansas in 1857 to get a better understanding of the violence and to show some support for the free-state forces. He did not stay in Kansas long, but his journey certainly represented a spirit of the times. Whether it was those of the Emigrant Aid Society who flocked to Kansas, filibusters who invaded Cuba, young men who set out to sea (like Herman Melville and Henry George), gold miners who travelled cross country, or countless other examples, Chet's ill-defined trip to Kansas was symbolic of the adventurous ambition of his generation.

Arthur had many other qualities that speak to Goodheart's description. The poor country bumpkin reinventing himself as a debonair, well-paid urban lawyer stands out. His willingness to fight for politics can be seen not only in his serving as quartermaster general of New York State during the Civil War, but in how he setup a maypole in 1844 to support the Whig presidential candidate Henry Clay. When some young Democrats came to knock it down, Arthur led a counterattack of young Whigs that resulted in a fistfight. Arthur joined the militia, like many of his generation. Unlike Ellsworth who took his pre-war militia duty seriously, Arthur seemed predominately interested in what we today call "networking." He built his list of legal clients and met other rising politicos. Finally, Arthur's break with the past and political convictions can be seen in how quickly he joined the brand new Republican Party. Like many of his cohort the war purged Arthur of his romantic idealism, much as World War I would do for a later generation.

A Blog Dedicated to the Study of the Gilded Age, Progressive Era, and history of the environment.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Monday, December 26, 2011

Europe's Sewer

On page 146 of The Rhine: An Eco-Biography , 1815-2000, Mark Cioc writes, "One hundred fifty years of hydraulic tinkering had turned the Rhine into a soulless shadow of its former self. Once clean, it was now filthy; once broad, it was now narrow; once bursting with life, it was now half-dead." Cioc chronicles how the once mythical and enchanting Rhine was altered in the wake of Napoleon and industrial revolution to become nothing more than a canal. The Rhine Commission, created in 1815, took decisions out of the hands of politicians and placed them in those of engineers who cared little for their environmental impact. They narrowed and straightened the Rhine, removing its islands and shortening it. The tamed Rhine, confined to a single riverbed supplied water, waste removal, power, industrial processes, transportation, and recreation. This last was given least priority. The engineers minimized their handy work on some of more touristy lengths, but gave no consideration to birds, fish, and mammals. In altering the flood plain birds lost much of their habitat. By chopping up the Rhine into dammed segments, the engineers made it impossible for migrating fish to reach their habitats. If the engineers were uninterested in preserving nature, the statesmen were less so. Driven by the Prussians, the main political concern was to foster growth to Germany's economic and military power. The chemical, coal, and dye industries pumped millions of tons of waste in the Rhine. Instead of regulating these emissions, industrial and political leaders adhered to the discredited notion that significant water would dilute the toxic waste. The effect, however, was to kill off more wildlife habitat and to turn some of the feeder rivers into the foulest stretches of water in the world. Conservation came late in Germany, long after the United States. As Cioc chronicles, the first effective pollution controls were only implemented in the 1970s and 1980s. The good news is this new regime is working to vastly reduce pollution. Restoring wildlife is proving much more difficult. Although some of the damage can be mitigated, the Rhine will never be what it once was.

Saturday, December 24, 2011

A private not a corporal

Although it falls on the tail end of the Progressive Era, World War I is one of my favorite historical topics. As I tell my students we are still living out the consequences of this momentous event. Today we see the effects most clearly in the Middle East where the borders were drawn when the victorious allies carved up the Ottoman Empire. The war left its lasting legacies on all the other participant nations as well. France was weakened, England confused, America disgusted, Russia communized, Germany punished, Italy betrayed, Austria-Hungary divided, Romania enlarged, Bulgaria reduced, and new states created. Tens of millions were killed, maimed, psychologically traumatized, and dehumanized. Civilians suffered atrocities and revolution followed in the wake of the war. It is hard to see how anyone of that generation was unaffected in someway.

Thomas Weber's Hitler's First War: Adolph Hitler, the Men of the LIst Regiment, and the First World War seeks to measure the impact of the First World War on the man most responsible for starting the even more terrible Second World War. I first got interested in this book when I read a summary of Weber's findings on a blog (HNN's Clio, I think). I admit I like books that spin conventional wisdom on its head. Later I heard Marshall Poe interview Weber on his excellent "New Books in History" podcast. It sounded like good historical grunt work and a window in to the life of front line soldiers. Weber chronicles the entire regiment in order to provide context for Hitler's experience. His primary theses is that the war did not make Hitler a Nazi. There was no outstanding sense of anti-semitism or proto-fascist/authoritarian sentiment in the unit. In fact, using the area the List veterans lived in (rural Bavaria), their religion (mostly Catholic), and individual accounts they were indeed less likely to become members of the Nazi party than other Germans. There were a few notable exceptions, of course, as some of Hitler's closest comrades took advantage of his rising power.

Weber finds that Hitler's ideology at the end of the war was a fuzzy fascination with the mixture of collectivism and nationalism, but few specific ideas. He first participated in the Bavarian Soviet which quickly collapsed. After the collapse of the revolutionary left, Hitler migrated to the revolutionary right. The mixture of collectivism and nationalism provided the bridge. Mein Kampf, therefore, was an attempt to cover up this left ward experience and root his ideology closely in a national experience that fit the tenets of his new party.

Weber makes many other arguments as well. Here is a sample.

*Hitler was not a frontline runner dodging machine gun bullets, but a "rear area pig" who had a comfy billet in the regimental HQ behind the lines.

*The regiment had few volunteers, it consisted mostly of reservists and high command considered it low quality unit to be used only when no other was on hand.

*His Iron Crosses owed much to this proximity to regimental officers.

*Hitler was only mildly injured from the gas attack of 1918 and that his injuries were psychosomatic, another fact of his past that Hitler wanted to conceal.

*An oddball loner from Austria with few social skills and no leadership abilities, he was promoted only one grade during the entire war. Never a corporal, he spent the whole war a private.

Thomas Weber's Hitler's First War: Adolph Hitler, the Men of the LIst Regiment, and the First World War seeks to measure the impact of the First World War on the man most responsible for starting the even more terrible Second World War. I first got interested in this book when I read a summary of Weber's findings on a blog (HNN's Clio, I think). I admit I like books that spin conventional wisdom on its head. Later I heard Marshall Poe interview Weber on his excellent "New Books in History" podcast. It sounded like good historical grunt work and a window in to the life of front line soldiers. Weber chronicles the entire regiment in order to provide context for Hitler's experience. His primary theses is that the war did not make Hitler a Nazi. There was no outstanding sense of anti-semitism or proto-fascist/authoritarian sentiment in the unit. In fact, using the area the List veterans lived in (rural Bavaria), their religion (mostly Catholic), and individual accounts they were indeed less likely to become members of the Nazi party than other Germans. There were a few notable exceptions, of course, as some of Hitler's closest comrades took advantage of his rising power.

Weber finds that Hitler's ideology at the end of the war was a fuzzy fascination with the mixture of collectivism and nationalism, but few specific ideas. He first participated in the Bavarian Soviet which quickly collapsed. After the collapse of the revolutionary left, Hitler migrated to the revolutionary right. The mixture of collectivism and nationalism provided the bridge. Mein Kampf, therefore, was an attempt to cover up this left ward experience and root his ideology closely in a national experience that fit the tenets of his new party.

Weber makes many other arguments as well. Here is a sample.

*Hitler was not a frontline runner dodging machine gun bullets, but a "rear area pig" who had a comfy billet in the regimental HQ behind the lines.

*The regiment had few volunteers, it consisted mostly of reservists and high command considered it low quality unit to be used only when no other was on hand.

*His Iron Crosses owed much to this proximity to regimental officers.

*Hitler was only mildly injured from the gas attack of 1918 and that his injuries were psychosomatic, another fact of his past that Hitler wanted to conceal.

*An oddball loner from Austria with few social skills and no leadership abilities, he was promoted only one grade during the entire war. Never a corporal, he spent the whole war a private.

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Chester Arthur isn't worth a $1?

The Treasury Department announced that it will cease making $1 coins after minting one portraying our 20th president, James A. Garfield. Of course, his successor via assassination, Chester A. Arthur will not enjoy the honor of a presidential coin. Perhaps conspiracy theorists will

speculate that this is some sort of payback for Arthur's complicity in the questions raised over our current president's citizenship. But the simple fact is Americans don't use the $1 coin and it has no place in our pockets, change cups, and cash registers. I admit I am guilty of this myself. The metallic images of Presidents Washington, Jefferson, and Hayes have a permanent residence in my desk draw with a commemorative token from Buffalo Bill's grave in Golden, Colorado and some sort of Soviet coin with Lenin's image and the dates 1870-1970 that my uncle smuggled back from a 1980s trip to the USSR (and yes, that was during the height of the "spy dust" years, if one recalls that Cold War news nugget). They haven't even made their way to my modest coin collection to cozy up to Susan B. Anthony, yet another $1 coin fiasco. My Irish grandmother made sure I received a freshly minted one as my interest history was already evident in 1979. I added it to my currency collection which then consisted of a couple of buffalo back

nickels and a $2 bill that I received on my birthday and never spent. I still have the $2 bill and the Susan B. Anthony dollar, and right there you can see I have taken $6 whole dollars permanently out of circulation. As a tax payer I am glad that we will no longer waste money creating a product that the public-at-large does not want or use. The historian in me, however, wishes they would have realized this a bit later, after coins bearing the images of the Gilded Age presidents could be minted and, to use a not quite appropriate term, circulated. Perhaps it would have stimulated some interest among some Americans in the Gilded Age and its bearded and mustached chief executives. Theodore Roosevelt would have been a good breaking point. After all, I would think Mount Rushmore would more than compensate for his not being on a coin.

speculate that this is some sort of payback for Arthur's complicity in the questions raised over our current president's citizenship. But the simple fact is Americans don't use the $1 coin and it has no place in our pockets, change cups, and cash registers. I admit I am guilty of this myself. The metallic images of Presidents Washington, Jefferson, and Hayes have a permanent residence in my desk draw with a commemorative token from Buffalo Bill's grave in Golden, Colorado and some sort of Soviet coin with Lenin's image and the dates 1870-1970 that my uncle smuggled back from a 1980s trip to the USSR (and yes, that was during the height of the "spy dust" years, if one recalls that Cold War news nugget). They haven't even made their way to my modest coin collection to cozy up to Susan B. Anthony, yet another $1 coin fiasco. My Irish grandmother made sure I received a freshly minted one as my interest history was already evident in 1979. I added it to my currency collection which then consisted of a couple of buffalo back

nickels and a $2 bill that I received on my birthday and never spent. I still have the $2 bill and the Susan B. Anthony dollar, and right there you can see I have taken $6 whole dollars permanently out of circulation. As a tax payer I am glad that we will no longer waste money creating a product that the public-at-large does not want or use. The historian in me, however, wishes they would have realized this a bit later, after coins bearing the images of the Gilded Age presidents could be minted and, to use a not quite appropriate term, circulated. Perhaps it would have stimulated some interest among some Americans in the Gilded Age and its bearded and mustached chief executives. Theodore Roosevelt would have been a good breaking point. After all, I would think Mount Rushmore would more than compensate for his not being on a coin.

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Decision Points

Theodore Roosevelt created the modern presidential autobiography. He stressed his accomplishments, minimized his setbacks, and offered insight to his decisions. In the years after 1913 it might have seemed Roosevelt's reflection on his life and presidency was a product of his own prolific authorial nature and not a new trend for former chief executives. William Howard Taft did not want to relive his unhappy four years in office, nor did he have a history of writing. Stricken with a stroke Woodrow Wilson could not write an autobiography. What a shame! His sense of history, writing ability, and professorial bent, could have produced a standout among presidential memoirs, even if it would have been burdened by his self-righteousness. Warren Harding died in office, but one wonders if he would have written one had he lived. Calvin Coolidge revived the memoir,

although it was not very informative. I remember reading Allen Nevins once wondered aloud why on earth Coolidge even bothered to write it. Herbert Hoover left a much more detailed, informative, and lengthy contribution. In this highly defensive work, Hoover sought to vindicate his reputation and offer his version of history. He divided the depression down to a number of smaller segments that he dealt with. Throughout he stuck to the narrative that he thoroughly understood what was going on and acted appropriately. Obviously, it all went to hell with the New Deal Democrats. Thereafter, all presidents who survived their terms wrote autobiographies or memoirs, mostly with the help of ghost writers. Each one has its own character and offers an insight to the presidents who wrote them. For example, Harry Truman's is homey, Dwight Eisenhower's is professional if bland, Nixon's is defensive and consumed by Watergate, and Clinton's is verbose.

Like his predecessors George W. Bush seeks to minimize his defeats and accent his Triumphs in his Decision Points. Skipping detailed discussion of individual policy, I will only offer a couple of general comments on the structure of the book.

1. I sensed that there were two myths Bush consciously sought to confront without mentinoing. First, Dick Cheney's name appears sporadically in the policy discussions. In other words, the Vice President does not appear to exert the same level of influence in Bush's account of his years in office as the media depicted. Second, it was largely reported during his administration that the president avoided internal discussion and debate. In his memoir, Bush recounts many debates within the administration and with allies on important policy matters. Of course, the gate swings both ways. If the president consulted many advisors then they must also take some of the blame for failed policies.

2. The organization of the book works well. It is thematic, not chronological. Nevertheless, I was disappointed that there was no discussion on environmental policies. No one is going to rank Bush as a great environmental president, but that still doesn't mean that Clear Skies, the protected zone in the Pacific, emissions standards, Global Warming, etc., were not worth more mention.

3. I liked the sense of humor. There are many serious topics and having a little humor (largely absent in most other presidential autobiographies) helps to cut some of Bush's defensiveness.

although it was not very informative. I remember reading Allen Nevins once wondered aloud why on earth Coolidge even bothered to write it. Herbert Hoover left a much more detailed, informative, and lengthy contribution. In this highly defensive work, Hoover sought to vindicate his reputation and offer his version of history. He divided the depression down to a number of smaller segments that he dealt with. Throughout he stuck to the narrative that he thoroughly understood what was going on and acted appropriately. Obviously, it all went to hell with the New Deal Democrats. Thereafter, all presidents who survived their terms wrote autobiographies or memoirs, mostly with the help of ghost writers. Each one has its own character and offers an insight to the presidents who wrote them. For example, Harry Truman's is homey, Dwight Eisenhower's is professional if bland, Nixon's is defensive and consumed by Watergate, and Clinton's is verbose.

Like his predecessors George W. Bush seeks to minimize his defeats and accent his Triumphs in his Decision Points. Skipping detailed discussion of individual policy, I will only offer a couple of general comments on the structure of the book.

1. I sensed that there were two myths Bush consciously sought to confront without mentinoing. First, Dick Cheney's name appears sporadically in the policy discussions. In other words, the Vice President does not appear to exert the same level of influence in Bush's account of his years in office as the media depicted. Second, it was largely reported during his administration that the president avoided internal discussion and debate. In his memoir, Bush recounts many debates within the administration and with allies on important policy matters. Of course, the gate swings both ways. If the president consulted many advisors then they must also take some of the blame for failed policies.

2. The organization of the book works well. It is thematic, not chronological. Nevertheless, I was disappointed that there was no discussion on environmental policies. No one is going to rank Bush as a great environmental president, but that still doesn't mean that Clear Skies, the protected zone in the Pacific, emissions standards, Global Warming, etc., were not worth more mention.

3. I liked the sense of humor. There are many serious topics and having a little humor (largely absent in most other presidential autobiographies) helps to cut some of Bush's defensiveness.

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

The Nature of New York

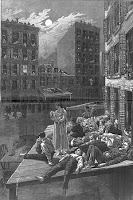

In my "The Ides" posting I noted how good intentions can sometimes boomerang with devastating effects. One example is an 1879 New York State law that required all apartment rooms to have a window. The idea behind the law was to bring light and fresh air to the overcrowded city tenements. This good sounding law had the unintended consequence of inspiring landlords to construct the infamous "dumbbell" apartment design (see picture to right). This odious

construction only made the problem worse as the windows in the "air shafts" between the buildings filled with rotting garbage and refuse. Instead or bringing fresh air and light, this law ironically created dank apartments infused with noxious fumes. I learned about this law in David Stradling's The Nature of New York: An Environmental History of the Empire State (Cornell, 2010).

As Stradling demonstrates, New York state played a pivotal role in the history of the American environment. Just to name some of the most important events and ideas emanating from the Empire State that inspired the nation: the Erie Canal, Niagara Falls tourism, Central Park, Adirondack State Park, Levittown, and Love Canal. Important individuals such as James Fenimore Cooper, the Hudson River School, the Roosevelts, Robert Marshall, and Robert Moses, to name a few, came from New York but impacted attitudes and policies throughout the United States. Being so focused on William Hornaday, I would argue that Stradling could have emphasized the role of the New York Zoological Park (a.k.a Bronx Zoo) in revolutionizing the concept of the zoo much more than he did, but I admit this falls in the category of basing criticism on how I might have written the book which is not always fair.

There are many more common environmental issues in New York State that could be used to make comparisons to other localities, states, and systems. Examples include, How to supply cities with water? Where to build infrastructure? Who should be held responsible for misdeeds and damage that harms other people? How to adapt to changes in the environment? What is the difference between genuine natural space and managed space? Throw in NIMBY, polluters, and larger trends like the decline of agriculture or the rise of the urban population and this book speaks across the Empire State's borders.

I really enjoyed The Nature of New York, especially because Stradling gives a lot of attention to the urban environment. He successfully argues that use of urban space is as legitimate topic for environmental history as forests, mountains, prairies, and tidal lands. New York City's pioneering 1916 zoning law stood out for me. I was surprised it took so long for such a code, and thought it more than coincidental that it was implemented only 4 years before the census revealed that the population of the country was equally divided between urban and rural dwellers. It is almost as if cities only then earned some respect as more than a dumping ground. Second, I just about forgot how much I enjoyed place histories. Whether it is a discussion on the history of the environment or politics, I do so enjoy this type of study.

construction only made the problem worse as the windows in the "air shafts" between the buildings filled with rotting garbage and refuse. Instead or bringing fresh air and light, this law ironically created dank apartments infused with noxious fumes. I learned about this law in David Stradling's The Nature of New York: An Environmental History of the Empire State (Cornell, 2010).

As Stradling demonstrates, New York state played a pivotal role in the history of the American environment. Just to name some of the most important events and ideas emanating from the Empire State that inspired the nation: the Erie Canal, Niagara Falls tourism, Central Park, Adirondack State Park, Levittown, and Love Canal. Important individuals such as James Fenimore Cooper, the Hudson River School, the Roosevelts, Robert Marshall, and Robert Moses, to name a few, came from New York but impacted attitudes and policies throughout the United States. Being so focused on William Hornaday, I would argue that Stradling could have emphasized the role of the New York Zoological Park (a.k.a Bronx Zoo) in revolutionizing the concept of the zoo much more than he did, but I admit this falls in the category of basing criticism on how I might have written the book which is not always fair.

There are many more common environmental issues in New York State that could be used to make comparisons to other localities, states, and systems. Examples include, How to supply cities with water? Where to build infrastructure? Who should be held responsible for misdeeds and damage that harms other people? How to adapt to changes in the environment? What is the difference between genuine natural space and managed space? Throw in NIMBY, polluters, and larger trends like the decline of agriculture or the rise of the urban population and this book speaks across the Empire State's borders.

I really enjoyed The Nature of New York, especially because Stradling gives a lot of attention to the urban environment. He successfully argues that use of urban space is as legitimate topic for environmental history as forests, mountains, prairies, and tidal lands. New York City's pioneering 1916 zoning law stood out for me. I was surprised it took so long for such a code, and thought it more than coincidental that it was implemented only 4 years before the census revealed that the population of the country was equally divided between urban and rural dwellers. It is almost as if cities only then earned some respect as more than a dumping ground. Second, I just about forgot how much I enjoyed place histories. Whether it is a discussion on the history of the environment or politics, I do so enjoy this type of study.

Thursday, December 1, 2011

Hot Time in the Old City

I recently reviewed Edward Kohn's Hot Time in the Old Town on H-Net's SHGAPE network. Here is the link if you are interested: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=33113.

Hot Time in the Old Town covers New York City's killer heat wave of 1896. Over 1200 people by the author's account. It reaches a little bit in claiming that the heat wave killed William Jennings Bryan's campaign and inspired Theodore Roosevelt's progressivism. Otherwise, this is an enjoyable and interesting read. The best part was in how it connected the lives of individuals, especially

tenement dwelling immigrants with the urban environment. Although I reviewed this for the Gilded Age and Progressive Era network, this book could work well for an environmental history course.

Hot Time in the Old Town covers New York City's killer heat wave of 1896. Over 1200 people by the author's account. It reaches a little bit in claiming that the heat wave killed William Jennings Bryan's campaign and inspired Theodore Roosevelt's progressivism. Otherwise, this is an enjoyable and interesting read. The best part was in how it connected the lives of individuals, especially

tenement dwelling immigrants with the urban environment. Although I reviewed this for the Gilded Age and Progressive Era network, this book could work well for an environmental history course.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Before Earth Day

Another one of those books I bought at ASEH and am just finishing is Before Earth Day: The Origins of American Environmental Law, 1945-1970 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009) by Karl B. Brooks.

Brooks argues that historians have placed too much emphasis on the environmental laws of the Johnson and Nixon Administrations. Instead, Brooks studies the period between the end of World War II and Earth Day and finds many important precedents. Little credited federal laws (the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 and the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1946, for example) and numerous state laws enacted in the late 1940s and early 1950s formed the foundation of post-war environmental law. Two things happened in this early period. First, states enacted many laws, proving the theory that they were the laboratories of reform. While some of these laws pushed the federal government to take a more aggressive stand on some issues, many made their way to the court and judicial review. Second, executive agencies empowered to administer environmental laws (on both state and federal levels) received greater authority to make changes and new regulations without having to go back to the legislative bodies. Thus, laws begat more laws, more judicial review, and more regulations. The process repeated itself until the accumulation of new codes required some adjustment. This is where Brooks sees the important legislation of the 1960s and 1970s coming in. They were not revolutionary responses to Rachel Carson, but critical clarifications to an existing body of law. As a byproduct, he makes a case that Eisenhower was good president on environmental matters.

My biggest question for this book is why start in 1945? As James Tober argues in Who Owns the Wildlife (1981) a substantial body of law related to wildlife developed in the late 19th century. There was a Supreme Court case, Geer vs. Conntecticut (1896) that ruled wildlife essentially belonged to the state. The decision of Missouri vs. Holland (1920) upheld the federal power to enforce wildlife regulations. And there were important laws throughout the early twentieth century affecting the environment and wildlife in particular, many of which empowered the executive agencies to form regulations. What affect did these laws have on the post-war evolution of environmental law?

Brooks argues that historians have placed too much emphasis on the environmental laws of the Johnson and Nixon Administrations. Instead, Brooks studies the period between the end of World War II and Earth Day and finds many important precedents. Little credited federal laws (the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 and the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1946, for example) and numerous state laws enacted in the late 1940s and early 1950s formed the foundation of post-war environmental law. Two things happened in this early period. First, states enacted many laws, proving the theory that they were the laboratories of reform. While some of these laws pushed the federal government to take a more aggressive stand on some issues, many made their way to the court and judicial review. Second, executive agencies empowered to administer environmental laws (on both state and federal levels) received greater authority to make changes and new regulations without having to go back to the legislative bodies. Thus, laws begat more laws, more judicial review, and more regulations. The process repeated itself until the accumulation of new codes required some adjustment. This is where Brooks sees the important legislation of the 1960s and 1970s coming in. They were not revolutionary responses to Rachel Carson, but critical clarifications to an existing body of law. As a byproduct, he makes a case that Eisenhower was good president on environmental matters.

My biggest question for this book is why start in 1945? As James Tober argues in Who Owns the Wildlife (1981) a substantial body of law related to wildlife developed in the late 19th century. There was a Supreme Court case, Geer vs. Conntecticut (1896) that ruled wildlife essentially belonged to the state. The decision of Missouri vs. Holland (1920) upheld the federal power to enforce wildlife regulations. And there were important laws throughout the early twentieth century affecting the environment and wildlife in particular, many of which empowered the executive agencies to form regulations. What affect did these laws have on the post-war evolution of environmental law?

Monday, November 21, 2011

William Temple Hornaday and the Progressive Era Nature Study Movement

Finally clearing out some of the books I bought at the ASEH conference in April, and just finished Kevin Armitage's The Nature Study Movement: The Forgotten Popularizer of America's Conservation Ethic (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009).

Armitage examined the Progressive Era nature study movement and concluded that it was a primarily a romantic movement (not a scientific one), that questioned modernity. I see that this is especially true of men like Thornton Burgess, William Temple Hornaday, and Ernest Thompson Seton, just to name some of those I am more familiar with. Although Hornaday was the dean of American zoologists during the thirty years he served as director of the Bronx Zoo (1896-1926), he was hardly a devoted scientist. In fact, he waged a personal war against what he considered the corrupting influences of the Teutonic scientific method. He criticized the academic scientists for removing nature study from the field and taking it to the laboratory, and for replacing buckskins and guns with lab coats and microscopes. Hornaday's scientific ideal was more grounded in a 19th century generalist movement. He felt the proper experience of wildlife took place in the outdoors where one observed animals whole, not in parts.

Yet, Hornaday had a very quirky attitude. While denying a certain fashion of science, he still maintained he followed the scientific principles and methods. He strongly criticized Reverend William Long and the nature fakers for ascribing unnatural skills to animals. But, no one anthropomorphized animals more than Hornaday himself. He ascribed a wide variety of human emotions to animals. Wolves were criminals, for example. Read his Wild Animal Interviews (1928) for a series of fictional conversations he had with animals. It is great stuff, and quite humorous (he was a funny man, a trait often overlooked in accounts of him), but it is not science. In Minds and Manners of Wild Animals (1922) he attempted to rate animal intelligence. Although maintaining he followed the scientific method, it is obvious that his data resulted not from verifiable tests, but from a lifetime of accumulated observations and anecdotes repackaged as objective truth. All this could be overlooked more easily if he had not spent much of his career attacking other people's views of science.

Hornaday's entire wildlife conservation program was based on the assumption that modernity, through improved firearms (pump and automatic shotguns) and transportation (automobiles) improved humanity's killing exponentially, while animals breeding remained an arithmetical calculation. Yes, that was a Malthusian view. Hornaday believed there would be no wildlife by 1950 at the rate at which human killing capacity improved.

Armitage does an excellent job of tying together various strands of the nature study movement. Back to rural living, bird day, gardening, woodcraft, etc., all receive their due. And he also explains how this nature study movement fit so well with the new curriculum of progressive education, as developed by John Dewey and others. Our generation is not the first to feel their children do not spend enough times outdoors. Hornaday had little interaction with Dewey or the progressive educators, but followed some of their ideas. Over 44 million people visited the Bronx Zoo during Hornaday's tenure as director. Many of them were school children who came on field trips. In this way Hornaday's zoo was one of the greatest contributors to the nature study movement.

Armitage examined the Progressive Era nature study movement and concluded that it was a primarily a romantic movement (not a scientific one), that questioned modernity. I see that this is especially true of men like Thornton Burgess, William Temple Hornaday, and Ernest Thompson Seton, just to name some of those I am more familiar with. Although Hornaday was the dean of American zoologists during the thirty years he served as director of the Bronx Zoo (1896-1926), he was hardly a devoted scientist. In fact, he waged a personal war against what he considered the corrupting influences of the Teutonic scientific method. He criticized the academic scientists for removing nature study from the field and taking it to the laboratory, and for replacing buckskins and guns with lab coats and microscopes. Hornaday's scientific ideal was more grounded in a 19th century generalist movement. He felt the proper experience of wildlife took place in the outdoors where one observed animals whole, not in parts.

Yet, Hornaday had a very quirky attitude. While denying a certain fashion of science, he still maintained he followed the scientific principles and methods. He strongly criticized Reverend William Long and the nature fakers for ascribing unnatural skills to animals. But, no one anthropomorphized animals more than Hornaday himself. He ascribed a wide variety of human emotions to animals. Wolves were criminals, for example. Read his Wild Animal Interviews (1928) for a series of fictional conversations he had with animals. It is great stuff, and quite humorous (he was a funny man, a trait often overlooked in accounts of him), but it is not science. In Minds and Manners of Wild Animals (1922) he attempted to rate animal intelligence. Although maintaining he followed the scientific method, it is obvious that his data resulted not from verifiable tests, but from a lifetime of accumulated observations and anecdotes repackaged as objective truth. All this could be overlooked more easily if he had not spent much of his career attacking other people's views of science.

Hornaday's entire wildlife conservation program was based on the assumption that modernity, through improved firearms (pump and automatic shotguns) and transportation (automobiles) improved humanity's killing exponentially, while animals breeding remained an arithmetical calculation. Yes, that was a Malthusian view. Hornaday believed there would be no wildlife by 1950 at the rate at which human killing capacity improved.

Armitage does an excellent job of tying together various strands of the nature study movement. Back to rural living, bird day, gardening, woodcraft, etc., all receive their due. And he also explains how this nature study movement fit so well with the new curriculum of progressive education, as developed by John Dewey and others. Our generation is not the first to feel their children do not spend enough times outdoors. Hornaday had little interaction with Dewey or the progressive educators, but followed some of their ideas. Over 44 million people visited the Bronx Zoo during Hornaday's tenure as director. Many of them were school children who came on field trips. In this way Hornaday's zoo was one of the greatest contributors to the nature study movement.

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Review of Wind Across the Everglades (1958)

In Wind Across the Everglades a game warden named Walt Murdock (played by Christopher Plummer) confronts plume hunter Cottonmouth Smith (played by Burl Ives) in early 1900s Florida. It is based loosely on the experiences of Guy Bradley, an Audubon warden who was killed by a plume hunter (also named Smith) in 1905. The Smith in the movie does not kill the game warden, although he made several failed attempts to rig a "natural" death. The cinematic game warden differed from the real one in ways other than that he survived his confrontation with his Smith. As where Bradley was a native Floridian familiar with the 'glades, Murdock is well educated northerner (often referred to as a "Yankee" when not called "Bird Boy") who came to Miami to teach natural history at the high school. He was fired literally as soon as he gets off the train because he pulled some plumes off one a woman's hat. This immediately draws him to the one Audubon representative in Miami who convinced the judge to release Murdock to serve as a warden in the Everglades. The views of the business community are crystallized in two individuals. One wants to profit from the plume trade, the other wants to drain the Everglades to make room for development. In contrast, Murdock becomes instantly infatuated with the swamps and rejects both of these positions.

In many ways I find the market hunter Smith the more interesting character. He leads a colony of violent outlaws, the misfits of society who believe their lifestyle is both the ultimate expression of individualism and a form of protest against modern society. Smith holds sway over this community as a sort of king. He is lord of nature and man in the swamp. He dispenses justice as he sees fit, punishes transgressions, and holds the power over life and death. In the end he miraculously decides to bring the "Bird Boy," as he calls Murdock to Miami and risk prosecution, but as he went to grab his hat he was bit by a snake and died with a buzzard circling overhead. This is a Hollywood movie after all!

Having read a great deal on the Progressive Era wildlife conservation movement, I really enjoyed this film. I think it captures a lot of the indifference that existed to the plumage issue at the time as well as the crusading spirit that motivated the early conservationists. By casting Murdock as a "Yankee" in the south, it also captured some of the conflict between local and outside values over nature that exist in conservation battles. But, I think the depiction of the market hunters is a little off. Many were family men following a tradition of their fathers and who shot game (for plumes or meat) to make extra money. This is not to defend them, but by and large they were much more ordinary than Smith's counter-cultural Robin Hood's band of the Swamps.

If I was teaching an environmental history class I think I would try to incorporate this film into the syllabus somehow. It could be a good vehicle for discussion on the points I enumerated above. As far as the film is concerned, the cinematography is phenomenal, especially given the date. There are many great scenes of wildlife and swamps, and there are no computer generated heron flocks in this movie.

In many ways I find the market hunter Smith the more interesting character. He leads a colony of violent outlaws, the misfits of society who believe their lifestyle is both the ultimate expression of individualism and a form of protest against modern society. Smith holds sway over this community as a sort of king. He is lord of nature and man in the swamp. He dispenses justice as he sees fit, punishes transgressions, and holds the power over life and death. In the end he miraculously decides to bring the "Bird Boy," as he calls Murdock to Miami and risk prosecution, but as he went to grab his hat he was bit by a snake and died with a buzzard circling overhead. This is a Hollywood movie after all!

Having read a great deal on the Progressive Era wildlife conservation movement, I really enjoyed this film. I think it captures a lot of the indifference that existed to the plumage issue at the time as well as the crusading spirit that motivated the early conservationists. By casting Murdock as a "Yankee" in the south, it also captured some of the conflict between local and outside values over nature that exist in conservation battles. But, I think the depiction of the market hunters is a little off. Many were family men following a tradition of their fathers and who shot game (for plumes or meat) to make extra money. This is not to defend them, but by and large they were much more ordinary than Smith's counter-cultural Robin Hood's band of the Swamps.

If I was teaching an environmental history class I think I would try to incorporate this film into the syllabus somehow. It could be a good vehicle for discussion on the points I enumerated above. As far as the film is concerned, the cinematography is phenomenal, especially given the date. There are many great scenes of wildlife and swamps, and there are no computer generated heron flocks in this movie.

Sunday, October 30, 2011

The Ides: Caesar's Murder and the War for Rome

As they say in Monty Python, "And now for some thing completely different." I do teach a course on Western Civilization I every spring and do devote a considerable amount of reading time to that subject. I recently completed Stephen Dando-Collins, The Ides: Caesar's Murder and the War for Rome. Earlier I read and posted on his book concerning the great fire of Rome during Nero's reign. Dando-Collins is an engaging writer who draws the reader into the Ancient Rome.

There are two points Dando-Collins makes in The Ides I wish to call attention to in this posting. First, Julius Caesar was not a benevolent dictator out improve the lives of the poor. He was, instead, and accurately, a power hungry dictator who played the politics of class with the best of them. One of the many mistakes his assassins made was their failure to win over the populace, something Caesar excelled at. In fact, it was his ability to win over the populace at the expense of the senatorial class that motivated his assassins. Personally, I think this message needs to be amplified. If there is one thing I fear about our current political situation is that I really do hear people (including friends) say we need a benevolent dictator. It is my belief that there is no such thing as a benevolent dictator.

Second, Caesar's assassins had no real post-assassination plan. It appears they put absolutely no thought into it. Their largest concern was in not being charged with murder. For this reason they focused on tyranicide, which was not a crime under Roman law. Cicero, who was not part of the plot, felt they should have knocked off Mark Anthony as well. Undoubtedly he was correct, but to kill Anthony would have been murder. The assassins made no provisions for amassing troops and had no real plans to restore the Republic. Anthony walked into this void and showed them to be, in the vernacular of my students, total noobs. When Octavian entered the scene it further complicated the lives of the assassins. Now there were two men vying for Caesar's dictatorial legacy. And both parties wanted to punish the assassins. There is a real message here: Think out your actions! History is full of such examples. Please feel free to share your favorite example of an action driven by the best motives that totally backfired.

There are two points Dando-Collins makes in The Ides I wish to call attention to in this posting. First, Julius Caesar was not a benevolent dictator out improve the lives of the poor. He was, instead, and accurately, a power hungry dictator who played the politics of class with the best of them. One of the many mistakes his assassins made was their failure to win over the populace, something Caesar excelled at. In fact, it was his ability to win over the populace at the expense of the senatorial class that motivated his assassins. Personally, I think this message needs to be amplified. If there is one thing I fear about our current political situation is that I really do hear people (including friends) say we need a benevolent dictator. It is my belief that there is no such thing as a benevolent dictator.

Second, Caesar's assassins had no real post-assassination plan. It appears they put absolutely no thought into it. Their largest concern was in not being charged with murder. For this reason they focused on tyranicide, which was not a crime under Roman law. Cicero, who was not part of the plot, felt they should have knocked off Mark Anthony as well. Undoubtedly he was correct, but to kill Anthony would have been murder. The assassins made no provisions for amassing troops and had no real plans to restore the Republic. Anthony walked into this void and showed them to be, in the vernacular of my students, total noobs. When Octavian entered the scene it further complicated the lives of the assassins. Now there were two men vying for Caesar's dictatorial legacy. And both parties wanted to punish the assassins. There is a real message here: Think out your actions! History is full of such examples. Please feel free to share your favorite example of an action driven by the best motives that totally backfired.

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Colonel Roosevelt

Ever since my father took me to the TR birthplace when I was 10 or 11 the Rough Rider has been my favorite American historical figure. Frequent trips to Sagamore Hill, about a 20 minute drive from our house on Long Island, fostered my growing interest with TR. Naturally, I turned to biographies which in turn led me to the study of the Progressive Era.

Theodore Roosevelt has had his fair share of biographers, ranging from flat out hagiograpies to the far less flattering variety. I just finished Colonel Roosevelt, the third and final installment in Edmund Morris's expansive biography of Theodore Roosevelt. I really wish I could turn a sentence like Morris. He has a great style and wit. Yes, wit, not snark. I know some historians have criticized him for not providing enough historiographical context, a fair comment, but he more than compensates in my opinion by drawing such a vivid human portrait. The Roosevelt I came away with from the book is a man very much lost in the world, uncertain of his place, and struggling to remain relevant.

I think Roosevelt redefined the post-presidency. Prior to him past presidents led fairly quiet lives out of the public eye. Roosevelt, on the other hand, continued to publish books, essays, op-ed pieces, and reviews. He made his opinions known on a wide variety of topics. He traveled the world, going on safari in Africa, hobknobing with European royalty, and exploring the Amazonian jungles. Heck, he even ran for president on a third party. Grover Cleveland, of course, ran for president, but he did that on a major party ticket, and had intended on running from the moment he left the White House in 1889. Ulysses Grant unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination in 1880. TR may have lost the 1912 election, but he did change the political landscape. Woodrow Wilson abandoned many of his own New Freedom ideas in favor of TR's New Nationalism.

In one other important way, TR served as a harbinger for future post-presidents. He spent a significant amount of time managing his legacy. In some ways his battle with his hand picked successor, William Howard Taft, was as much about legacy as any thing else. In reversing part of his predecessor's conservation policy, Taft was also attacking that cherished legacy. Roosevelt defended his legacy with a his Autobiography, another trend he established for post-presidents. Beyond that TR used his other writings to support and re-interpret his positions and attack his detractors. He even sued a newspaper writer who alleged he drank too much.

Theodore Roosevelt has had his fair share of biographers, ranging from flat out hagiograpies to the far less flattering variety. I just finished Colonel Roosevelt, the third and final installment in Edmund Morris's expansive biography of Theodore Roosevelt. I really wish I could turn a sentence like Morris. He has a great style and wit. Yes, wit, not snark. I know some historians have criticized him for not providing enough historiographical context, a fair comment, but he more than compensates in my opinion by drawing such a vivid human portrait. The Roosevelt I came away with from the book is a man very much lost in the world, uncertain of his place, and struggling to remain relevant.

I think Roosevelt redefined the post-presidency. Prior to him past presidents led fairly quiet lives out of the public eye. Roosevelt, on the other hand, continued to publish books, essays, op-ed pieces, and reviews. He made his opinions known on a wide variety of topics. He traveled the world, going on safari in Africa, hobknobing with European royalty, and exploring the Amazonian jungles. Heck, he even ran for president on a third party. Grover Cleveland, of course, ran for president, but he did that on a major party ticket, and had intended on running from the moment he left the White House in 1889. Ulysses Grant unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination in 1880. TR may have lost the 1912 election, but he did change the political landscape. Woodrow Wilson abandoned many of his own New Freedom ideas in favor of TR's New Nationalism.

In one other important way, TR served as a harbinger for future post-presidents. He spent a significant amount of time managing his legacy. In some ways his battle with his hand picked successor, William Howard Taft, was as much about legacy as any thing else. In reversing part of his predecessor's conservation policy, Taft was also attacking that cherished legacy. Roosevelt defended his legacy with a his Autobiography, another trend he established for post-presidents. Beyond that TR used his other writings to support and re-interpret his positions and attack his detractors. He even sued a newspaper writer who alleged he drank too much.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Wild Horses of the American West

Monday, August 15, 2011

A Gilded Age lesson about the Flat Tax

I was sitting at dinner with my family the other night and the I overheard a discussion about the flat tax at the next table. My mind drifted back to another era, the Gilded Age and the contentious issue of the tariff.

In the presidential election of 1880, the Democratic candidate, General Winfield Scott Hancock, uttered a gaffe when he called the tariff a local issue. Republican opponents seized on this statement as an example of the General's obvious ignorance in economic policies. How, they asked, could the the trade policy that drove the national economy, contributed so much to the federal coffers, and protected the jobs of millions of workers be remotely considered local? Well Hancock might not have been clear in his meaning, but the historian can see much accuracy in his statement. The tariff was the sum of many rates on thousands of items, which was the product of political deals to that often had the goal of satisfying local constituencies. In other words, no matter how much the Democrats of Louisiana supported a tariff on principle - as sound Democrats were expected to do - they inevitably opposed lowering the rates on sugar imports from the Caribbean or the Philippines out of fear it would damage their local economies. In other words, local political considerations trumped ideals.

The tariff, however, did not exist in a vacuum. As American industry grew in the late 1880s and early 1890s a new economic concern developed. Instead of fearing competition from cheap markets, American industries had so dominated the home market, that they became troubled by the idea that would build up an excess of product they could not sell. They not only feared the loss of revenue and economic decline from a shut down, but also the attendant social unrest, especially after the Haymarket Square riot of 1886. Moreover, they were concerned about another type of surplus, too much money in the federal treasury. In a deflationary period, having money collecting dust in a federal vault was a net loss to the economy.

To deal with this the Republicans came up with one novel idea and one not so new one. The novel idea was to reform the tariff to include a reciprocity agreement clause. This would allow the president to negotiate trade deals outside the normal tariff rules. It was you scratch my back and I will scratch yours kind of arrangement. I always considered this a really clever way of dealing with a real policy conundrum. How to keep a protectionist tariff (increasingly sold as a jobs saving measure) and lower the rates at the same time? Reciprocity provided the answer. At the same time, the McKinley Tariff of 1890 (named after then Congressman and future president William McKinley) lowered or eliminated rates on consumer items to reduce the surplus. Exports significantly increased as President Benjamin Harrison negotiated agreements with other countries to exchange specific items at lower rates. The less novel approach was the old fashion idea of lets eliminate the surplus by spending it. In this case, increasing payments to Civil War pensioners and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act that had the United States government purchasing nearly all the silver mined in the country. How is that for a subsidy! Such lavish spending earned the 51st Congress the sobriquet, the Billion Dollar Congress.

After having let the Republicans take a whack at the problem of surplus, the public turned to the Democrats. Grover Cleveland, elected in 1892, then entered one of the most miserable terms of office experienced by any president, as the economy crashed within months of his having taken office. Cleveland lowered spending, by eliminating the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, and attempted a tariff reform. His proposal called for replacing revenue lost from general rate reductions with an income tax. Congress, however, proved incapable of producing the reform he demanded. Instead, it was a case of each member of Congress protecting the interest of their district. Cleveland was disgusted, but there was little he could do. In the end the Wilson-Gorman Tariff became law without the president's signature.

Why did a nearby discussion on the flat tax make me think of the tariff as an issue over one hundred and twenty years prior? I think it is because of the one striking similarity between today's tax code and the tariff of those days. It is no coincidence that as the tariff faded away the income tax replaced it. Not only as the government's source of revenue, but also as one of the chief means in which lawmakers can encourage local businesses. Instead of raising the rates on their foreign competitors, we give them a tax break as an incentive. I am little bit more of a loss to explain how the tariff was used to encourage people to engage in certain behaviors, in the way that the current tax code promotes home ownership and higher education, and, for whatever reason, corporate jets, but I might think of one if I was not so tired at the moment :-)

In the presidential election of 1880, the Democratic candidate, General Winfield Scott Hancock, uttered a gaffe when he called the tariff a local issue. Republican opponents seized on this statement as an example of the General's obvious ignorance in economic policies. How, they asked, could the the trade policy that drove the national economy, contributed so much to the federal coffers, and protected the jobs of millions of workers be remotely considered local? Well Hancock might not have been clear in his meaning, but the historian can see much accuracy in his statement. The tariff was the sum of many rates on thousands of items, which was the product of political deals to that often had the goal of satisfying local constituencies. In other words, no matter how much the Democrats of Louisiana supported a tariff on principle - as sound Democrats were expected to do - they inevitably opposed lowering the rates on sugar imports from the Caribbean or the Philippines out of fear it would damage their local economies. In other words, local political considerations trumped ideals.

The tariff, however, did not exist in a vacuum. As American industry grew in the late 1880s and early 1890s a new economic concern developed. Instead of fearing competition from cheap markets, American industries had so dominated the home market, that they became troubled by the idea that would build up an excess of product they could not sell. They not only feared the loss of revenue and economic decline from a shut down, but also the attendant social unrest, especially after the Haymarket Square riot of 1886. Moreover, they were concerned about another type of surplus, too much money in the federal treasury. In a deflationary period, having money collecting dust in a federal vault was a net loss to the economy.

To deal with this the Republicans came up with one novel idea and one not so new one. The novel idea was to reform the tariff to include a reciprocity agreement clause. This would allow the president to negotiate trade deals outside the normal tariff rules. It was you scratch my back and I will scratch yours kind of arrangement. I always considered this a really clever way of dealing with a real policy conundrum. How to keep a protectionist tariff (increasingly sold as a jobs saving measure) and lower the rates at the same time? Reciprocity provided the answer. At the same time, the McKinley Tariff of 1890 (named after then Congressman and future president William McKinley) lowered or eliminated rates on consumer items to reduce the surplus. Exports significantly increased as President Benjamin Harrison negotiated agreements with other countries to exchange specific items at lower rates. The less novel approach was the old fashion idea of lets eliminate the surplus by spending it. In this case, increasing payments to Civil War pensioners and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act that had the United States government purchasing nearly all the silver mined in the country. How is that for a subsidy! Such lavish spending earned the 51st Congress the sobriquet, the Billion Dollar Congress.

After having let the Republicans take a whack at the problem of surplus, the public turned to the Democrats. Grover Cleveland, elected in 1892, then entered one of the most miserable terms of office experienced by any president, as the economy crashed within months of his having taken office. Cleveland lowered spending, by eliminating the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, and attempted a tariff reform. His proposal called for replacing revenue lost from general rate reductions with an income tax. Congress, however, proved incapable of producing the reform he demanded. Instead, it was a case of each member of Congress protecting the interest of their district. Cleveland was disgusted, but there was little he could do. In the end the Wilson-Gorman Tariff became law without the president's signature.

Why did a nearby discussion on the flat tax make me think of the tariff as an issue over one hundred and twenty years prior? I think it is because of the one striking similarity between today's tax code and the tariff of those days. It is no coincidence that as the tariff faded away the income tax replaced it. Not only as the government's source of revenue, but also as one of the chief means in which lawmakers can encourage local businesses. Instead of raising the rates on their foreign competitors, we give them a tax break as an incentive. I am little bit more of a loss to explain how the tariff was used to encourage people to engage in certain behaviors, in the way that the current tax code promotes home ownership and higher education, and, for whatever reason, corporate jets, but I might think of one if I was not so tired at the moment :-)

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Wild Horses

A few notes about horses in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era I learned in J. Edward De Steiguer's Wild Horses of the West: History and Politics of America's Mustangs (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2011).

During the mid-19th century the wild horse population numbered about 2.5 million animals. They descended from Spanish horses that escaped the missions in the 17th and 18th Century either on their own or with the aid of Native Americans. Combined with millions of buffalo and cattle, the hoofed animals did significant damage to the fragile ecosystem. During the Gilded Age their range shrunk as cattle ranches and farms moved further west. One of the forces protecting the wild horses was the great open breeding programs. Cowboys preferred to send their horses out to the wild herds to breed. But a series of disasters decreased the demand for new horses. Although De Steiguer does not mention it, I think the Blizzards of 1886-88 had to have had some effect on the horse population. Not so much from the snow itself, but the effect it had on the cattle industry and thus the need for mounts. De Steiguer does attribute a decline in horse demand to the depression of 1893 and the automobile, which seem reasonable enough. What remained of the wild horses were sold off in several large shipments, mainly to the British Army during the Boer War and later during World War I. Those animals not shipped off to war, fared no better. Although the total horse population in American reached its zenith in 1920 at 20 million head, the wild percentage of the total would shrink even more dramatically. As prosperity spread, people purchased homes and pets, wild horses were round up and slaughtered for pet food and glue, made into baseball covers, and canned for food to be sold in overseas markets. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 with its fencing provisions vastly compounded the ill fortunes of the wild horse. By channelling horses off of farm land and funneling them into an increasingly narrow area, they became easier prey for the slaughterers. By 1940 they were about gone.

During the mid-19th century the wild horse population numbered about 2.5 million animals. They descended from Spanish horses that escaped the missions in the 17th and 18th Century either on their own or with the aid of Native Americans. Combined with millions of buffalo and cattle, the hoofed animals did significant damage to the fragile ecosystem. During the Gilded Age their range shrunk as cattle ranches and farms moved further west. One of the forces protecting the wild horses was the great open breeding programs. Cowboys preferred to send their horses out to the wild herds to breed. But a series of disasters decreased the demand for new horses. Although De Steiguer does not mention it, I think the Blizzards of 1886-88 had to have had some effect on the horse population. Not so much from the snow itself, but the effect it had on the cattle industry and thus the need for mounts. De Steiguer does attribute a decline in horse demand to the depression of 1893 and the automobile, which seem reasonable enough. What remained of the wild horses were sold off in several large shipments, mainly to the British Army during the Boer War and later during World War I. Those animals not shipped off to war, fared no better. Although the total horse population in American reached its zenith in 1920 at 20 million head, the wild percentage of the total would shrink even more dramatically. As prosperity spread, people purchased homes and pets, wild horses were round up and slaughtered for pet food and glue, made into baseball covers, and canned for food to be sold in overseas markets. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 with its fencing provisions vastly compounded the ill fortunes of the wild horse. By channelling horses off of farm land and funneling them into an increasingly narrow area, they became easier prey for the slaughterers. By 1940 they were about gone.

Saturday, July 16, 2011

William T. Hornaday and the Uses of Personal Papers

Just getting back from a week in Washington spent in the manuscript collections of the Library of Congress's Madison Building. Unlike the absolutely stunning (and distracting, I would argue) main reading room in the Jefferson building, the manuscript room in the Madison building is

functional and plain. The staff was very helpful and knowledgable. I worked my way through two collections. First, the William T. Hornaday Papers, and, second, a much smaller piece of the Irving Brant Papers. Although remembered mostly for his authoratative biography of James Madison, Brant began his writing career as a free lance journalist. While researching an article on the Audubon Society he met Hornaday, fell under the older man's sway, and served as his lobbyist in Washington for several years in the early 1930s. Brant also wrote pamphlets for the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC), an organization directed by Rosalie Edge specializing in radical conservation pamphlets. The ECC echoed Hornaday's philosophy and he provided advice, moral support, and money. He also gave them information, something they as relative newcomers desperately needed.

And this leads me, by way of lengthy preamble, to the main point of this posting. As much as anyone possibly could, Hornaday consciously constructed a personal archive with the intent of influencing future generations. He genuinely believed that by 1950 only the English sparrow would survive and he wanted to record his efforts at trying to save wildlife, while, at the same time, finger the short sighted conservationists who refused to heed his warnings. Along the way he constructed many scrapbooks of letters, newspaper clippings (he hired a service to send him clippings from all over the country, an early version of RSS), magazine articles, congressional hearings and bills, etc. The most telling portions of the scrapbooks, are his hand written comments in the margins and along the tops of pages to inform intended readers of important developments. He found use of them in his own lifetime, such as when the young journalist Irving Brant needed information on the Audubon Society for an article he was writing. Hornaday essentially said, "You want information. I have plenty." All of it, of course, was damning evidence of how the Audubon Society betrayed the conservation movement in 1911 by accepting money from gun makers (see my posting here) and throughout the 1920s by supporting a migratory bird refuge bill that contained a provision for adding public shooting grounds to the refuges. Brant read the scrapbooks and became a lifelong convert to conservation. A couple of years later, in 1929, Horndaday shared his scrapbooks with Rosalie Edge, who, too, became an instant ally, fellow traveler, and critic of the Audubon Society. Hornaday shared his scrapbooks and documents with others, and his papers served as the archives for a militant, radical, and anti-establishment brand of conservation in the late 1920s and early 1930s. As he approached dotage and failing health, he made provision to send this archive of scrapbooks and personal letter books to the archives of the New York Zoological Park. Currently, it is the Wild Life Conservation Society, and that is where you will find his choicest conservation writings.

What about his private papers, the 39,000 other documents, now in the Library of Congress (LOC)? Here, too, one sees conscious effort to shape a view of the past. He annotated some letters with block lettering with messages for others. Other materials have notes relating on how he wanted to incorporate information into his autobiography. The LOC contains the total mess known as Eighty Fascinating Years, his unpublished autobiography, where several drafts are thrown together with different chapter headings, pagination, etc. Then there is lots of stuff he probably never wanted any historian to see. Amid the superfluous items (old car repair bills, heating bills, and thousands of pages of petty and routine correspondence) there were some real gems for the biographer. He gave advice to his daughter, some of which goes a great way to explaining his paradoxical behaviors. For example, how was some one so gregarious and friendly also so prickly and quick to cast off friends? There were many letters to his wife (some of them surprisingly bawdy) that shed light on his marriage. His personal letterbooks say a lot about his family relations, friendships, and commitments outside of work and conservation. I have always been impressed with Hornaday's appetite for work, but now I am even more impressed given his social commitments. Most heartbreaking of all is a letter from his mother, sick and dying in Indiana, writing to say she could actually brush her hair that day, even though someone had to write the letter for her. It was probably the last one he received from his mother and he kept it his entire life.

The Brant Papers were also interesting, and helped me explode one lie, but you will have to wait for the book to hear about that one!

functional and plain. The staff was very helpful and knowledgable. I worked my way through two collections. First, the William T. Hornaday Papers, and, second, a much smaller piece of the Irving Brant Papers. Although remembered mostly for his authoratative biography of James Madison, Brant began his writing career as a free lance journalist. While researching an article on the Audubon Society he met Hornaday, fell under the older man's sway, and served as his lobbyist in Washington for several years in the early 1930s. Brant also wrote pamphlets for the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC), an organization directed by Rosalie Edge specializing in radical conservation pamphlets. The ECC echoed Hornaday's philosophy and he provided advice, moral support, and money. He also gave them information, something they as relative newcomers desperately needed.

And this leads me, by way of lengthy preamble, to the main point of this posting. As much as anyone possibly could, Hornaday consciously constructed a personal archive with the intent of influencing future generations. He genuinely believed that by 1950 only the English sparrow would survive and he wanted to record his efforts at trying to save wildlife, while, at the same time, finger the short sighted conservationists who refused to heed his warnings. Along the way he constructed many scrapbooks of letters, newspaper clippings (he hired a service to send him clippings from all over the country, an early version of RSS), magazine articles, congressional hearings and bills, etc. The most telling portions of the scrapbooks, are his hand written comments in the margins and along the tops of pages to inform intended readers of important developments. He found use of them in his own lifetime, such as when the young journalist Irving Brant needed information on the Audubon Society for an article he was writing. Hornaday essentially said, "You want information. I have plenty." All of it, of course, was damning evidence of how the Audubon Society betrayed the conservation movement in 1911 by accepting money from gun makers (see my posting here) and throughout the 1920s by supporting a migratory bird refuge bill that contained a provision for adding public shooting grounds to the refuges. Brant read the scrapbooks and became a lifelong convert to conservation. A couple of years later, in 1929, Horndaday shared his scrapbooks with Rosalie Edge, who, too, became an instant ally, fellow traveler, and critic of the Audubon Society. Hornaday shared his scrapbooks and documents with others, and his papers served as the archives for a militant, radical, and anti-establishment brand of conservation in the late 1920s and early 1930s. As he approached dotage and failing health, he made provision to send this archive of scrapbooks and personal letter books to the archives of the New York Zoological Park. Currently, it is the Wild Life Conservation Society, and that is where you will find his choicest conservation writings.

What about his private papers, the 39,000 other documents, now in the Library of Congress (LOC)? Here, too, one sees conscious effort to shape a view of the past. He annotated some letters with block lettering with messages for others. Other materials have notes relating on how he wanted to incorporate information into his autobiography. The LOC contains the total mess known as Eighty Fascinating Years, his unpublished autobiography, where several drafts are thrown together with different chapter headings, pagination, etc. Then there is lots of stuff he probably never wanted any historian to see. Amid the superfluous items (old car repair bills, heating bills, and thousands of pages of petty and routine correspondence) there were some real gems for the biographer. He gave advice to his daughter, some of which goes a great way to explaining his paradoxical behaviors. For example, how was some one so gregarious and friendly also so prickly and quick to cast off friends? There were many letters to his wife (some of them surprisingly bawdy) that shed light on his marriage. His personal letterbooks say a lot about his family relations, friendships, and commitments outside of work and conservation. I have always been impressed with Hornaday's appetite for work, but now I am even more impressed given his social commitments. Most heartbreaking of all is a letter from his mother, sick and dying in Indiana, writing to say she could actually brush her hair that day, even though someone had to write the letter for her. It was probably the last one he received from his mother and he kept it his entire life.

The Brant Papers were also interesting, and helped me explode one lie, but you will have to wait for the book to hear about that one!

Saturday, July 2, 2011

July 2, pt 2

On July 2, 1881 Charles Guiteau shot President James A. Garfield in the back at a Washington DC